Patterns of Decision Architecture

Organizational behaviors that improve decision quality

Decision Architecture is the structure we design, as an organization, when we “decide how to decide”. In our organizations today, decision making relies on (mostly) implicit, ad-hoc practices and methods. The quality and speed of the decisions that result is… well, about what you’d expect from a loose approach.

How can we set out to make our strategic decision making a little bit better?

We can start by exploring some patterns of good decision architecture, drawn from leading practitioners and thought leaders in business, psychology, and economics. We can then think about which problems and forces (described in the patterns) resonate the most, from within our current environments. Then we can learn some methods and practices listed in the solutions section, then try some things out within our leadership teams, to achieve a better result.

Remember, you already have a decision architecture today - it’s just “loose”. Your challenge is to make it a little better, via some continuous improvement.

Big change won’t happen overnight. And be aware that these are complicated social dynamics you're navigating. But what’s more important than good decisions? It’s worth the time and energy. So buckle up.

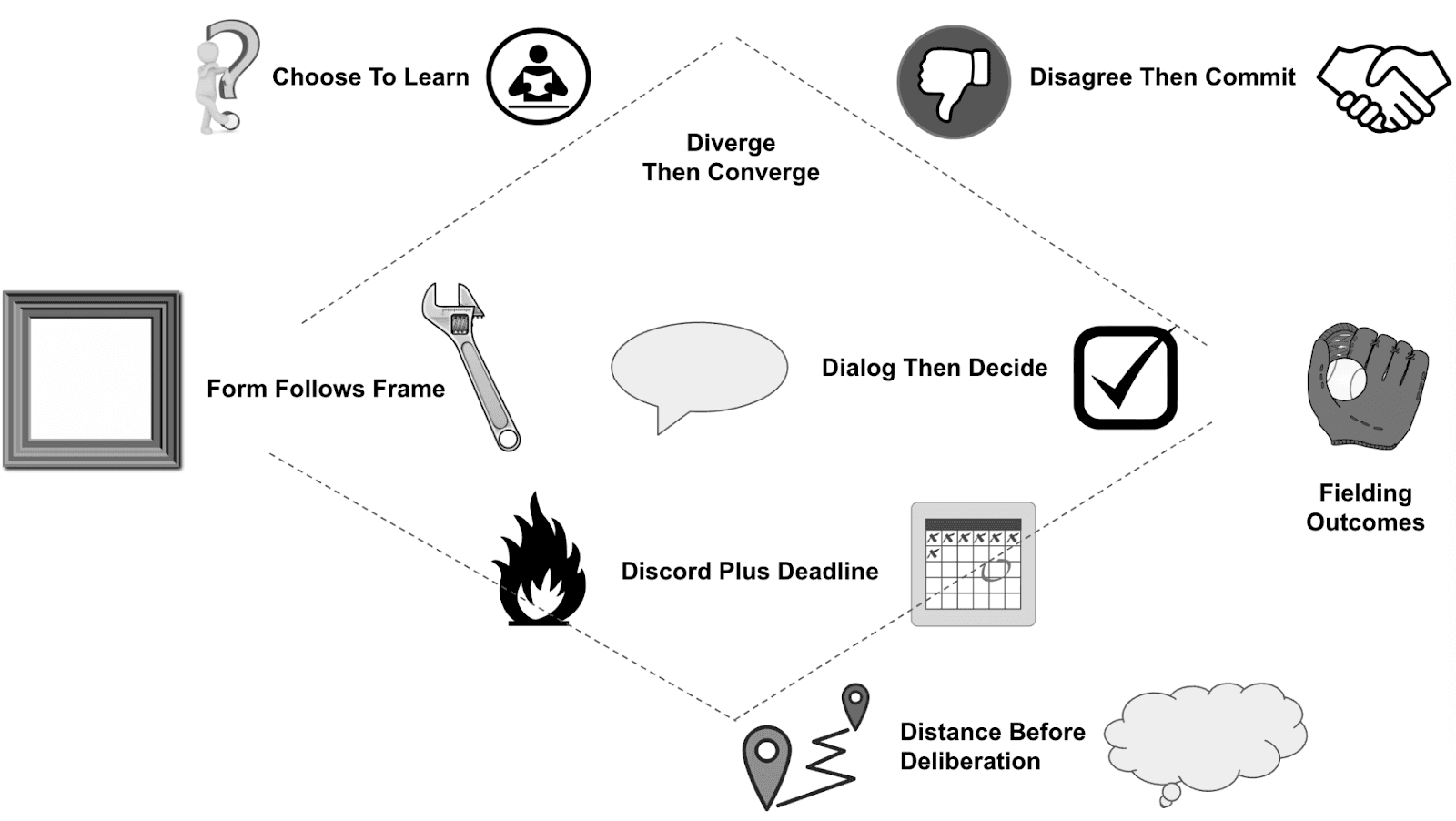

Here are the eight patterns we will introduce:

- “Form Follows Frame”

- “Choose to Learn”

- “Diverge then Converge”

- “Dialog then Decide”

- “Discord plus Deadline”

- “Distance before Deliberation”

- “Disagree then Commit”

- “Fielding Outcomes”

Form Follows Frame

Problem: Leaders apply one decision making approach to all kinds of decisions.

Conditions: Some decisions are bet-the-company big bets, some are cross-functional, cross-discipline, and cross-team, some are easily decentralized, and some are trivial. But the same approach is applied to each kind.

Forces:

- It is difficult to find the sweet spot between "too-much" process and "not-enough" process.

- It is harder to arrive at decisions when there are more stakeholders, and our relationships with them are weaker.

- When the stakes are higher, the lack of complete information becomes more uncomfortable.

Solution: Frame the decision type to help facilitate how to bring in the right people and the right information at the right time. Frame the decision in a way that explains why the decision matters, e.g. what/when/why, importance, urgency, and reversibility.

Result: With a decision-making approach that matches the need, the overall decisioning effectiveness of the organization improves.

Choose to Learn

Problem: Decisions made under uncertainty carry significant risk.

Conditions: Leaders commit to a decision, but then stop monitoring uncertainty-related risks.

Forces:

- Uncertainty forces assumptions, which should be monitored as new information comes to light.

- We value certainty so much that we hate to revisit made decisions.

- Revisiting a decision is also seen as a sign of weakness in a leader.

Solution: Create a leadership culture where acknowledging the uncertainty in a decision is the norm. Then make that uncertainty visible, to support follow-up monitoring and sense-making. Emphasize the validation of assumptions and hypotheses via short cycles of learning, to reduce uncertainty and mitigate risk.

- Value Engineering

- Tripwires

- Experimental Mindset - Build hypotheses around your work and goals, to frame it as an exploration, when causality is not clear.

Result: With a culture that makes uncertainty visible and manageable, leaders can make and communicate decisions more effectively, to drive better outcomes.

Diverge then Converge

Problem: Leaders tend to lock into a preferred choice too quickly in a decision-to-make

Conditions: When a viable choice is quickly suggested, especially by vocal leaders, it can inhibit a robust investigation into alternatives.

Forces:

- When a viable choice is suggested by vocal leaders, it can inhibit a broad investigation into alternatives.

- We naturally think in terms of “whether or not” decisions.

- An emphasis on decision velocity (which is good) might constrain spending time to explore new ideas.

- Mature teams develop a common worldview, and it’s not comfortable to invite outsiders to contribute more divergent thinking.

- Positive thinking as a culture can make it uncomfortable to suggest polar alternative that challenge the initial ideas.

Solution: Encourage divergent thinking by inviting in outside SMEs, forming nominal groups, establishing a “devil’s advocate” or “outside challenger” role, using the “vanishing options test”, and emphasizing the breadth, volume, and quality of ideas to form candidate choices.

Result: The leadership team has a repeatable approach to consistently collecting and evaluating a robust set of alternatives, to give greater confidence in the resulting decision.

Dialog then Decide

Problem: Decision meetings often end with no resolution, resulting in an endless series of followup meetings.

Conditions: Often a single meeting is scheduled around a decision-to-make. The single meeting then attempts to both discuss options and arrive at a decision.

Forces:

- Soliciting options for a decision-to-make is a creative activity where divergent thinking is desired.

- A dialog around the options helps clarify the choices and arrive at a shared understanding.

- A single accountable decision owner should be able to learn from the dialog, then make an informed choice.

Solution: Divide decision-making into two distinct events: (1) A dialog event where a nominal group reviews their independently sourced options, and (2) a decision event where the rationale for the choice is crafted and communicated to the participants to support shared commitment and execution.

Result: The first event encourages healthy debate, while the second event yields commitment.

Discord plus Deadline

Problem: Discussion and debate goes on too long, well past the point of adding new insight.

Conditions: Informal decision making practices, like “getting together to talk about it”. Vague accountability for deciding (i.e. unclear roles and responsibilities for decision making).

Forces:

- Decision makers find it difficult to talk about uncertainty

- “Not knowing” is seen as a weakness, so “known unknowns” are swept under the rug.

- Informal decision making practices, like “getting together to talk about it”, can allow for creativity but struggle with complexity.

- When there is vague accountability for "who decides" (i.e. unclear roles and responsibilities for decision making), then participants may discuss things indefinitely, waiting for someone to "step in"

Solution: In addition to setting clear accountability for deciding, set a deadline for when the decision should be made. From that, set an intermediate deadline for when discussion (divergence, debate, and discord) should stop, and the final stage of deciding begins.

Result: With a due date that signals the urgency and the timeframe for analysis and deliberation, decision makers can harness the energy of the group more effectively.

Distance before Deliberation

Problem: Short-term emotions and conflicted feelings can make it hard to get perspective on a decision.

Conditions: Facing a tough choice or a thorny dilemma, we can get blinded by the particulars and change our mind back and forth. In other cases, emotion drives too-quick decisions.

Forces:

- Emotion is stronger than rationality (System 1 over System 2).

- Humans are not always rational.

- Preference for the familiar (mere-exposure principle) and loss aversion dramatically strengthen the preservation of the status quo, or “the way things work today”.

Solution: Seek ways to get adequate perspective on a decision, to counter immediate emotion. Apply mental shifts to distance yourself and gain an outsider’s perspective on the decision-to-make. Leverage longer-term core beliefs to evaluate options.

- 10 / 10 / 10 Rule - Tackle tough decisions by asking yourself: “What will be the consequence(s) of my action/decision in 10 minutes, 10 months, and 10 years…?”

- Silent Meetings - Have employees submit notes and ideas ahead of time, then start with a table read of the summary, in silence, before discussion.

- Sleep On It - Wait on making a decision until the next day, to neutralize some emotional impact and get more perspective.

Result: Decision makers can get unstuck, and find the right balance to harness emotions with rationality.

Disagree then Commit

Problem: Leaders make decisions, but without the support and buy-in of key stakeholders.

Conditions: Decision makers have successfully encouraged healthy dissent during the dialog stage of decision making. A decision has been made, but some of the participants driving the dissent now disagree with the choice made.

Forces:

- When decision authority and/or decision roles are unclear, participants might assume that consensus is required, or that lack of consensus implies a lack of commitment to a decision.

- Some participants will continue support their option instead of committing to the decision made

Solution: Make explicit the decision authority, with a single person acting as Decider for a decision. Communicate that decisions in the presence of uncertainty should emphasize velocity and validation over extended debate.

- DACI Roles & Responsibilities

- Bargaining - Driving horse-trading amongst disagreeing parties until a compromise is reached. Costly, but effective for buy-in.

- Point Out Flaws - Sometimes the best way to defend a decision is to point out its flaws. It acknowledges that the choice still faces some uncertainty.

Result: Expectations and policies have clarified that once the choice is made, then healthy dissent must transition to buy-in and commitment to the choice, with full support for the implementation of the decision-made.

Fielding Outcomes

Problem: Leaders don't know how to assess their decision making ability.

Conditions: Leaders make decisions, then attribute the result to their decision, even when other factors were more likely to have driven the outcome. Leaders evaluate the quality of their decisions not by the effectiveness of the approach, but by the outcomes that result.

Forces:

- When we judge our decisions by their outcome, we freeze up and seek certainty (where that is impossible), and analysis paralysis reduces decision velocity.

- Organizations with informal decision architectures tend to judge the effectiveness of their decision making in terms of the outcomes that result.

- There is inherent uncertainty when trying to establish a relationship between a decision (possible cause) with an outcome (possible effect).

Solution: Periodically review outcomes to reflect and learn about the decision architecture. Acknowledge the uncertainty in tying an effect (outcome) to a cause (decision). Take deliberate effort to reflect on possible causality. When presented with an outcome, ask “do I feel that my decision drove this outcome? Or did luck have more to do with it” to evaluate the quality of the decision making.

- Belief Challenging

- Fielding Outcomes

- Five Why’s - An iterative interrogative technique used to explore the cause-and-effect relationships underlying a particular problem or result.

Result: A decision architecture that can assess the quality of decision making based on the process, not just the outcome.